Chapter 13

The Vatican Attempt to Prevent Peace

When the French started to crumble under the relentless blows of the Communists of Indo-China, the Catholic Church welcomed the U.S. intervention, hopefully expecting that the American presence would help expedite the conquest of the entire province. The Church had already been in the field combating a retroactive campaign against Red expansionism.

The military and ideological success of the Viet-Minhs, and the increasing popularity of their cause, upset the Vatican's hopes. It led to something which the Vatican had always opposed, namely the division of Vietnam into two halves—the North and the South. The Geneva Agreement, which sanctioned such division, therefore became anathema to Vatican strategists as much as it was to its supporters in the U.S. But whereas the U.S. came to accept the split in military and political terms, no matter how provisional, the Vatican never did so. It judged the division as a major setback almost as great as the defeat of the French.

The Vatican however, while rejecting the split of the country, continued to cooperate and indeed to encourage an ever deeper intervention of the U.S., the better to use American economic and military strength to carry on with the promotion of a unified Vietnam, where ultimately the Church would rule supreme, once the war had been won.

The Vatican never accepted the division of Vietnam, as envisaged by Geneva, because of the consistency of its general strategy. This could be identified with the pursuit of four main objectives: (1) the maintenance of the unity of Vietnam; (2) total elimination of communism; (3) Catholicization of the whole country; (4) the creation of a totalitarian Catholic state, to achieve and to maintain the first three.

Steps had been taken long before the division occurred for the concretization of such a policy. As we have already seen, it was the Vatican, with the help of the U.S. Catholic lobby headed by Cardinal Spellman, that initially propelled Diem into power. The powerful trio, namely Pius XII, Cardinal Spellman and John Foster Dulles, were behind the setting up of a semi-totalitarian regime in South Vietnam from its inception. It was they, in fact, who advised Diem to challenge the Geneva Agreement; to refuse to have the elections as promised to the people of Vietnam, in order to find out whether the Vietnamese people wanted unification or not.

We have seen what the disastrous result of such refusal portended for Vietnam and the U.S. itself. Subsequent efforts to reach some form of understanding with North Vietnam were consistently scotched by President Diem, upon the direct advice of the Vatican and of Washington. In July, 1955, according to the Geneva Agreement, Diem had been expected to begin consultations for the elections scheduled in 1956: "The conference declares that, so far as Vietnam is concerned, the settlement of political problems on the basis of respect for the principle of independence . . . national elections shall be held in July, 1956 under the supervision of an International Commission . . . "

The Republic of North Vietnam suggested to Diem that the pre-electoral consultative conference should be held. This was done in May and June, 1956, in July, 1957, in May, 1958 and again in July, 1959. The offer was to be negotiated between North and South Vietnam, on the basis of "free general elections by secret ballot." All such offers were rejected. Diem refused to have the election called for in Article 7 of the Declaration of the Geneva Agreements. The U.S. supported him fully. The result of such refusal was the disastrous civil war which ensued. American Senator Ernest Gruening, in a speech delivered to the U.S. Senate April 9, 1965, had this to say about it. "That civil war began . . . when Diem's regime—at our urging—refused to carry out the provision contained in the Geneva Agreement to hold elections for the reunification of Vietnam." The accusation of the Senator was correct. What he failed to tell the Senate, and thus to the American people however, was the fact that the real culprits responsible for such a breach of faith had not even been mentioned. This for the simple reason that they were active, behind the scenes, in the corridors of a secretive diplomacy, which was beyond the reach of the government.

It could not be otherwise. Since such secret diplomacy was the brainchild of a Church which was pursuing ideological objectives to ultimately aggrandize herself in the religious field. The better to conduct her policies, therefore, she had turned one of her representatives into a subtle relentless politician, who although never elected by any American voter, nevertheless could exert more influence in the conduct of American diplomacy than any individual in the House of Representatives, the Senate, or even the U.S. government itself. The name of such a person was Cardinal Spellman.

Cardinal Spellman was so identified with the Vietnam War that after he came out in the open prior to years of hidden promotional activities, he became the popular epitome of the war itself, and this to such an extent, that the Vietnam War eventually was labeled the Spellman War. This was not a scornful adjective. It was the verbal epitome of a concrete reality. Cardinal Spellman, as the personalized vehicle of the double Vatican-American strategy, had begun to represent the Catholic-American policy itself. To that effect he was fully endowed with the right attributes. He was the religious-military representative of both Catholic and military powers since he represented both, being the Vicar of the American Armed Forces of the U.S. He was always flown in American military aircraft, visited regularly the U.S. troops in Vietnam, and repeatedly declared, with the personal approval of both Pius XII and J.F. Dulles, that the U.S. troops in South Vietnam were: "the soldiers of Christ." Which in this context, being cardinal of the Catholic Church, meant soldiers of the Catholic Church.

During the conflict, while the North was attempting to reach some form of agreement with the South, the Vatican intervened again and again to prevent any kind of understanding between the two. This it did, by the most blatant use of religion. During the Marian Congress of 1959 held in Saigon, for instance, it consecrated the whole of Vietnam to the Virgin Mary. The consecration had been inspired by Rome.

This sealed for good any possibility of peaceful cooperation between North and South Vietnam, since to the millions of Catholics which had fled, the consecration of the whole of Vietnam to the Virgin had the gravest political implications. To them it meant one thing: no cooperation with the North. The following year, the Vatican went further and took an even more serious step. It was a well calculated move, which although seemingly of an ecclesiastical nature, yet had the most profound political implication. On December 8, 1960, the Pope established "an ordinary Catholic episcopal hierarchy for all of Vietnam." Thereupon, he took an even more daring step, he created an archdiocese in the capital of the Communist North itself.

This was done not by Pope Pius XII, the arch-enemy of communism and the architect of the original Vietnam religious-political strategy, who meanwhile had died in 1958, but by his successor, Pope John XXIII, the initiator of ecumenism and of goodwill to all men. The implication was that the Vatican considered the whole of Vietnam one indivisible country; which in this context meant that the North had to be joined with the South, ruled as it was by a devout son of the Church.

Sons, would have been a more realistic description, since South Vietnam, by now, had become the political domain of a single family, whose members had partitioned the land and the governmental machinery into fortresses from which to impose the Catholic yoke upon an unwilling population. President Diem was not only the official head of the government, he was also the head of a family junta composed of exceptionally zealous Catholics, who monopolized the most important offices of the regime. One brother, Ngo Dinh Luyen, ruled the province of the Cham minorities, another brother Ngo Dinh Can, governed central Vietnam, as a warlord from the town of Hue—the center of Buddhism. A third brother, Ngo Dinh Thuc, was the Catholic archbishop of the province of Thuathien. Yet another brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, a trade union leader, was the head of the semisecret Can Lao Movement, and the head of the fearful secret police. His wife was Madame Nhu, better known as The Dragon Lady. Her father became ambassador to the U.S. There were also nephews, nieces and others— all zealous Catholics. In addition to these, there were friends, army officers, judges, top Civil Service officials, all Catholics acting in total accordance with the Catholic Church and her objective. Seen from this angle, therefore, the Vatican moves were most significant in religious and political terms.

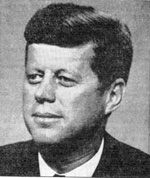

John F. Kennedy, first Catholic president of the U.S. Kennedy, as senator, was part of the Catholic lobby which pushed for the installation of a Catholic president in South Vietnam. As early as 1954-55 he advocated military intervention to help the French hold back Communist advancement in North Vietnam. He was instrumental in the installation of Ngo Dunh Diem as Prime Minister. When Kennedy became President, he rapidly escalated the U.S. military involvement in support of Diem's Catholic regime. Later when Diem's persecution of the Buddhists began to draw fire from world opinion, Kennedy had to choose between supporting his church's effort or promoting his own political career. He chose to pressure Diem to let up on the persecutions. Diem's Buddhist generals seized the opportunity to assassinate Diem. Three weeks later Kennedy himself fell to an assassin's bullet. |

This was so, not only because of the situation in Vietnam as a whole, and of South Vietnam in particular, but equally, because a no less portentous event, meanwhile, had occurred in the U.S. itself. The Kennedy Administration was taking over from President Eisenhower. Kennedy, the fervent Catholic lobbyist and supporter of Diem, set in earnest to promote the policy he had advocated for so long while still a Senator. It was no coincidence that as soon as he was in the White House, Kennedy escalated the U.S. involvement in South Vietnam. By the end of 1961, 30,000 Americans had been sent to Vietnam to prosecute the war, and thus indirectly to help Catholic Diem and his Catholic regime. A far cry from the mere 1,000 American advisors sent so reluctantly by his predecessor, Eisenhower. The result was that the "limited risk" gamble of President Eisenhower had been suddenly transformed into the "unlimited commitment" by the Catholic Diem sponsor, Catholic President Kennedy. It was the beginning of the disastrous American involvement into the Vietnam War.